Canine Transmissible Venereal Tumour

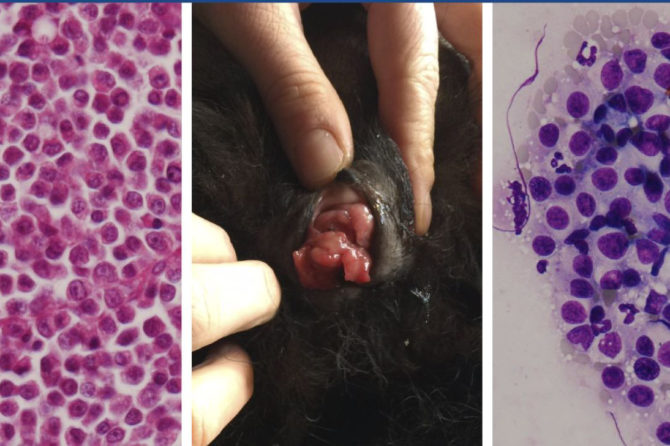

During our first castration and neutering project in the Balkans, we treated a female dog with a vaginal tumour. Apart from the tumour, she also had a heavy vaginal discharge, but was otherwise in a relatively good condition. At the time, we had no idea what we were dealing with. Our projects in the Balkans continued and we encountered similar pathology in both female and male dogs with increasing frequency. The Institute of Pathology at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Ljubljana kindly agreed to help us with the diagnostics, and soon it was confirmed that the tumours were indeed TVT. They confirmed the disease by performing cytology and histology tests.

As the name suggests, we are talking about transmissible tumours that affect dogs. It occurs in both female and male dogs and presents itself as ulcerating, pink formation or genital hypertrophy. TVT is found in dogs on all continents, although there is a higher incidence in countries with larger street dog populations. The incidence of TVT in developed countries has decreased considerably as an unintended consequence of the dog control laws. Dog castration and neutering are important preventative measures.

TVT is the oldest tumour known in nature. Its genome shows that it first appeared in a dog that lived about 11,000 years ago. Although slight variations of the genome do occur, all TVT tumours still carry the mutated genes of the “original host” – the dog that first gave rise to TVT.

In 1876, the Russian veterinarian Novinsky demonstrated that the tumour was spread by living tumour cells directly between two dogs, usually during coitus. Only 13% of these cells survive the transmission.

The mechanism used by TVT to escape the host’s immune system is not fully understood, although down-regulation of histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and recruitment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment play an important role.

It is very rare for the tumour to metastasize or cause the death of the dog.

Even though tumours can be removed surgically, there is a high tendency for its recurrence. Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice, most often with vincristine, vinblastine and doxorubicin, but radiotherapy and immunotherapy are also being used for treating TVT.

Our organization is primarily involved in castrating and neutering street dogs, so treating TVT can be rather challenging. If we want to use chemotherapy, the treated dog needs to have at least a temporary foster home, which is not always available. That is why we often choose to remove the tumours surgically.

The street dogs from the Balkans and other countries are getting adopted outside their countries of origin with ever increasing frequency. That is why the veterinarians from countries in which TVT does not occur are likely to come into contact with it. A while

ago, we were contacted by volunteers from a Dutch organization that helps the dogs in the Balkans, about a dog that had been adopted from Bosnia to the Netherlands. Although the dog had been neutered with an ovariectomy, she started bleeding from her vagina. Her owners suspected she had come into season and took her to a vet. After a second operation and a removal of the uterus, she continued bleeding. At this point they asked us for our opinion. We immediately suspected TVT and it turned out our diagnosis was correct. The dog was treated with chemotherapy and fully recovered.

Volunteer Group SVSP

Leave a reply